Blog

Leading IT Cybersecurity Adaption

James V. Tarlton

7/20/2025

Abstract

This literature review examines the critical role of human factors in cybersecurity leadership discussed by William J. Triplet (2022), revealing that humans constitute a weakness in organizational security with research indicating that over 86% of cyber incidents involve human error or misconduct. The analysis of current literature demonstrates that cybersecurity leaders face significant challenges in addressing unintentional human behaviors, communication gaps, and organizational cultural deficiencies that contribute to security vulnerabilities. Key findings indicate that traditional technology-centric approaches are insufficient, and organizations require transformational leadership approaches that prioritize human-centered security strategies, comprehensive training programs, and cultural transformation initiatives. Recommendations include implementing behavioral security models, establishing cross-functional insider threat teams, developing continuous security awareness programs, and creating cybersecurity culture maturity frameworks that position employees as active defenders rather than passive compliance actors.

Problem Statement

Triplett (2022) stresses that while organizations invest billions in technological solutions, human factors remain the primary source of security vulnerabilities and breaches. Additional research reveals multiple interconnected issues stemming from inadequate attention to human elements in cybersecurity strategy. First, there exists a persistent knowledge gap where leaders treat cybersecurity as purely a technological challenge rather than a sociotechnical problem requiring human behavior management (McEvoy & Kowalski, 2019). This narrow-mindedness results in cybersecurity leaders who possess strong technical competencies but lack the interpersonal, communication, and cultural transformation skills necessary to effectively engage with non-technical employees (Cole, 2022).

Second, organizational cultures often exhibit security immaturity. Prakash & Pearlson suggest that employees demonstrate complacent attitudes toward cybersecurity responsibilities when leaders fail to establish accountability structures (2024). The literature indicates that organizations operate at basic cybersecurity culture maturity levels where employees believe "technology teams will keep us safe" (p. 3) rather than embracing personal responsibility for security, Prakash & Pearlson add. Third, traditional security awareness training approaches demonstrate limited effectiveness, with studies showing no significant correlation between recent annual training completion and employee ability to avoid phishing attacks (UC, Dept. of Computer Science, 2025). Finally, insider threats represent a growing challenge that requires sophisticated human factors analysis and behavioral intervention strategies (Watts, 2024) (Sifma, 2024).

Problem Statement

The systematic literature review conducted by Triplett (2022) provides comprehensive evidence that unintentional human factors significantly impact cybersecurity effectiveness across organizations. Analysis of 15 studies revealed consistent patterns of human vulnerabilities including employees forgetting to log out of systems, creating weak passwords, and unknowingly clicking malicious links due to limited cybersecurity knowledge. These behaviors stem from deeper organizational factors including inadequate leadership attention to human behavior, insufficient communication between technical and non-technical staff, and workplace stress that contributes to security fatigue (Pollini, et al., 2022).

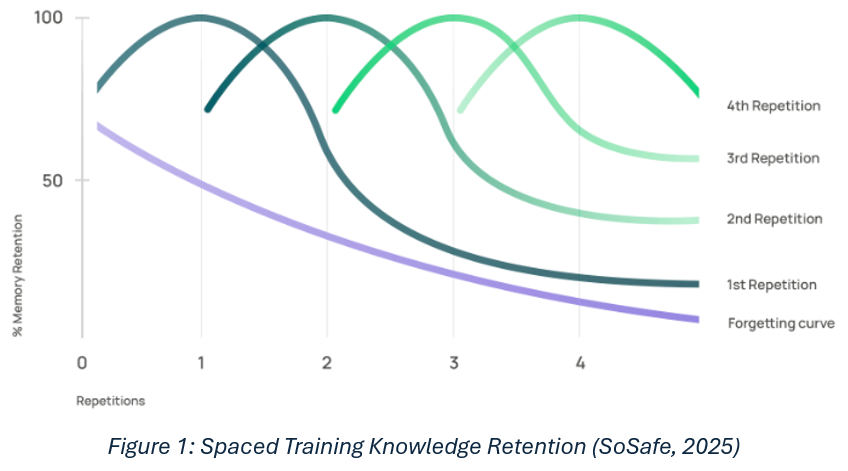

McEvoy & Kowalski (2019) agree with Triplett’s assessment, stating that the sociotechnical systems perspective reveals that cybersecurity risks emerge from complex interactions between individual, organizational, and technological factors. They also suggest that current risk analysis methodologies focus primarily on technical and procedural requirements while systematically excluding sociotechnical considerations. This leaves organizations vulnerable to predictable human-centered attacks. The Behavioral Security Model demonstrates that sustainable security requires addressing four interconnected dimensions: knowledge, context, motivation, and behavior (SOSafe, 2025). Organizations that fail to address these dimensions comprehensively experience persistent security vulnerabilities despite substantial technological investments.

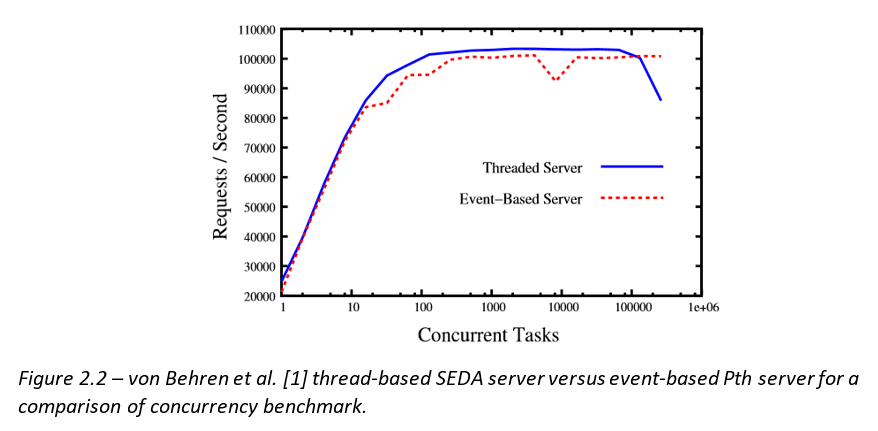

Per SoSafe, leadership competency analysis reveals significant gaps in cybersecurity leaders' ability to bridge technical and business domains while effectively communicating with diverse stakeholder groups. Moreso, SoSafe suggests managers facilitating repetitive training increases user memory retention (Figure 1). Research indicates that effective cybersecurity leaders require not only technical expertise but also business acumen, emotional intelligence, and transformational leadership capabilities (Corll, 2024) (Burton, et al., 2023). However, cybersecurity professionals are underrepresented in organizational leadership hierarchies and lack the social capital necessary to influence organizational behavior change. However, IT representation is trending upward (Llorca, 2024). Gartner suggests that 84% of the highest performing companies now include Chief Information Officers (CIOs) within their executive leadership teams (2025).

Nonetheless, the insider threat dimension presents particularly complex challenges requiring integration of human resources, legal, risk management, and cybersecurity functions. Watts (2024) suggests that organizations must distinguish between intentional and unintentional insider threats while implementing monitoring and intervention strategies that respect employee privacy and maintain organizational trust.

Alternative Solutions

Training and Awareness Enhancement Approaches

Research demonstrates that well-designed security awareness training can reduce phishing susceptibility from 60% to 10% within 12 months, with studies showing 80% of organizations reporting reduced staff susceptibility to phishing attacks (Daly, 2025). Continuous, behavior-focused training programs that incorporate psychological principles show promise for creating lasting behavioral change. Traditional annual training approaches show limited effectiveness, with recent studies finding no correlation between training recency and phishing resistance (UC, Dept. of Computer Science, 2025). Many training programs focus on knowledge transfer rather than behavior modification, resulting in awareness without corresponding behavioral change (HoxHunt, 2025).

Cybersecurity Culture Transformation Initiatives

Prakash & Pearlson’s (2024) culture maturity model provides structured framework for organizations to progress from basic security awareness to dynamic cybersecurity cultures where employees proactively identify and address threats. Everard (2025) suggests that cultural approaches address root causes of security vulnerabilities by aligning organizational values, attitudes, and beliefs with security objectives. However, Triplet (2022) stresses that culture transformation requires significant time investment and sustained leadership commitment, with outcomes difficult to measure quantitatively. Therefore, he suggests that cultural initiatives may face resistance from employees who view security requirements as burdensome rather than value-adding.

Technology-Enhanced Human Factors Management

Artificial intelligence and machine learning applications can identify behavioral anomalies and provide predictive insights for insider threat management, per Sifma (2024). Sifma also suggests that identity and access management systems can reduce human error by automating security controls and limiting exposure to mistakes. However, technology cannot address underlying behavioral human factors. Triplet (2022) and McEvoy & Kowalski (2019) suggest that over-reliance on technological solutions perpetuates the fundamental problem of treating cybersecurity as a technical rather than sociotechnical issues.

Leadership Development and Communication Enhancement

Developing cybersecurity leaders with strong communication and social skills enables better engagement with non-technical employees and executives (Corll, 2024). Leadership development programs can address the gap between technical expertise and business competencies (Triplet, 2022). However, it requires sustained investment and may not address systemic organizational issues contributing to security vulnerabilities. Leadership improvements may be insufficient without corresponding structural changes, per Triplet.

Recommendations / Reflection

Based on Triplet’s literature (2022), organizations should adopt an integrated Human-Centered Cybersecurity Leadership Framework that addresses technical and human dimensions of security. The priority is to implement a Behavioral Security Model which can address knowledge, motivation, and behavior with continuous learning programs that incorporate proven frameworks. Real-time feedback, social reinforcement, and practical exercises can help embed secure behaviors into daily routines.

A second recommendation is to establish cross-functional insider threat teams that bring together human resources, legal, privacy, risk management, and cybersecurity professionals. These professionals should address insider threats with an approach that stresses deterrence through a positive climate rather than relying solely on punitive measures. With transparency and trust, employees are encouraged to proactively report findings.

Third, leadership development must be prioritized to create transformational cybersecurity leaders. Effective leaders in this space require a blend of technical expertise, business acumen, and strong interpersonal skills. Leadership programs should emphasize emotional intelligence, adaptive communication, and motivation. Leaders who can bridge technical and non-technical gaps are better equipped to drive cultural change (Prakash & Pearlson, 2024).

Finally, organizations should invest in cybersecurity culture maturity assessment and development programs. These programs provide frameworks for enhancing the organization’s security culture, guiding the transition from basic compliance mindsets to dynamic, resilient cultures where all employees see themselves as active defenders (Everard, 2025). Technology alone is insufficient for sustainable security. True resilience requires a holistic approach that integrates behavioral science, cultural evolution, and leadership development. Organizations that commit to this comprehensive strategy will be better positioned to address evolving cyber threats, maintain operational effectiveness, and empower employees as essential partners in defense.

Bibliography

Burton, S. L., Burrell, D. N., Nobles, C., Jones, L. A., Illinois Institute of Technology, Capitol Technology University , & Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University. (2023). Exploring the Nexus of Cybersecurity Leadership, Human Factors, Emotional Intelligence, Inno Emotional Intelligence, Innovative Work Beha ork Behavior, and Critical , and Critical Leadership Traits. Scientific Bulletin, 28.

Cole, E. (2022, 2 10). How to be an Effective CISO by Being an Affective Communicator. Retrieved from secure-anchor.com/cybercrisis/: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jU2cQAxRodk&t=4s

Corll, B. (2024, 8 1). 5 behaviors for transforming your cybersecurity leadership. Retrieved from zscaler.com: https://www.zscaler.com/cxorevolutionaries/insights/5-behaviors-transforming-your-cybersecurity-leadership

Daly, J. (2025). How effective is security awareness training? Retrieved from usecure.io: https://blog.usecure.io/does-security-awareness-training-work

Everard, T. (2025). What is Cyber Security Culture and why does it matter for your organisation? Retrieved from paconsulting.com: https://www.paconsulting.com/insights/what-is-cyber-security-culture-and-why-does-it-matter-for-your-organisation

Gartner. (2025, 2 12). Gartner Executive FastStart for CIOs. Retrieved from gartner.com: https://www.gartner.com/en/chief-information-officer/insights/executive-faststart-cio

HoxHunt. (2025). How to Create Behavior Change With Security Awareness Training. Retrieved from hoxhunt.com: https://hoxhunt.com/lp/how-to-create-behavior-change-with-security-awareness-training

Llorca, M. (2024, 10 24). Today's CIO, Tomorrow's CEO: The Changing Landscape Of Corporate Leadership. Retrieved from forbes.com/councils/forbestechcouncil: https://www.forbes.com/councils/forbestechcouncil/2024/10/24/todays-cio-tomorrows-ceo-the-changing-landscape-of-corporate-leadership/

McEvoy, R., & Kowalski, S. (2019). Cassandra’s Calling Card: Socio-technical Risk Analysis and Management in Cyber Security Systems. CEUR Workshop Proceedings. vol. 2398. Retrieved from CEUR-WS.org/Vol-2398/Paper8.pdf

Pollini, A., Callari, T. C., Tedeschi, A., Ruscio, D., Save, L., Chiarugi, F., & Guerri, D. (2022). Leveraging human factors in cybersecurity: an integrated methodological approach. Cogn Technol Work, 371-390.

Prakash, M., & Pearlson, D. K. (2024). Cybersecurity Culture Maturity Model. Cybersecurity at MIT Sloan, MIT, CAMS24.1109.

Sifma. (2024, 7 1). Insider Threat Best Practices Guide, 3rd Ed. Retrieved from sifma.org: https://www.sifma.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/2024-SIFMA-Insider-Threat-Best-Practices-Guide-FINAL.pdf

SOSafe. (2025, 1 10). The Behavioral Security Model: A proactive approach to the human component of cyber security. Retrieved from sosafe-awareness.com: https://sosafe-awareness.com/en-us/blog/how-to-create-a-security-culture-the-behavioral-security-model/

Triplet, W. J. (2022). Addressing Human Factors in Cybersecurity Leadership. J. Cybersecur. Priv., 573–586.

UC, Dept. of Computer Science. (2025, 3 24). New Study Reveals Gaps in Common Types of Cybersecurity Training. Retrieved from cs.uchicago.edu: https://cs.uchicago.edu/news/new-study-reveals-gaps-in-common-types-of-cybersecurity-training/

Watts, L. (2024, 6 24). Unintentional Insider Threats: The Overlooked Risk. Retrieved from teramind.co/blog: https://www.teramind.co/blog/unintentional-insider-threat/

Beyond Voluntary IoT Standards

James V. Tarlton

6/11/2025

Abstract

The article "Cybersecurity Carrots and Sticks" by Hiller et al. (2024) address the persistent and worsening trend of cyberattacks, highlighting the limitations of current regulatory and voluntary approaches. The authors propose an incentive-based tax policy framework to spur stronger cybersecurity postures across the private sector. It involves combining tax credits (carrots) and penalties (sticks). This case analysis firstly evaluates the eƯectiveness of such an approach, drawing on Bruce Schneier’s examples and policy considerations to contextualize the urgency and complexity of the cybersecurity landscape. Schneier’s Click Here to Kill Everybody (2018) assesses risks emerging from the emergence of Internet of Things (IoT) devices. He systematically explores the causes of these security gaps and proposes a mix of policy, regulatory, and technical solutions. Secondly, this case analysis recommends prioritizing regulatory reform and realigning industry incentives. Which may help address the root causes of IoT insecurity. While Hiller et al.’s recommendations are robust and pragmatic, further global coordination and enforcement mechanisms are needed to fully meet the scale of the challenges outlined by Schneier.

Problem Statement

The central problem identified by Hiller et al. (2024) is the unsustainable spiral of cyberinsecurity in the United States, driven by a fragmented regulatory landscape, overreliance on self-regulation, and chronic underinvestment in cybersecurity, particularly among small and medium-sized enterprises. As Schneier (2018) illustrates, the rapid proliferation of IoT devices and the interconnectedness of critical infrastructure amplify these vulnerabilities, making the consequences of policy failures increasingly severe. He explains that manufacturers prioritize cost-savings over security. This leaves devices lacking the quality assurance needed (Matthews, 2017). And the lack of penalties for insecure products means companies have no incentive to change posture (Tjahja, 2022). Hiller et al. explain that existing regulatory frameworks are siloed by sector, leading to inconsistent oversight.

Case Analysis

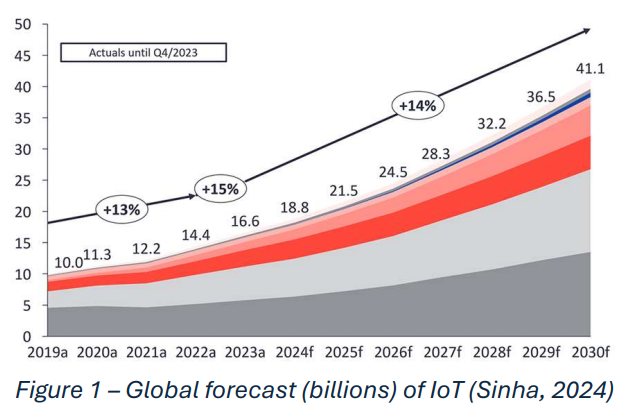

Hiller et al. document how each year brings record-breaking cyberattacks. The authors argue that negative externalities and information asymmetries lead to chronic underinvestment in cybersecurity. Schneier suggests that the rapid proliferation of IoT devices has expanded the attack vectors for malicious actors. Duarte states that in 2025 the worldwide sum of connected IoT devices will reach 30.9 B (2024). Internet+ interconnectedness enables vulnerabilities to cascade and amplify, Schneier adds; and as the number of devices grows, risk grows exponentially.

However, at the time of Schneier’s writing, Gartner’s 2020 projection of connected IoT devices reaching 20.5 B was an overestimation. Sinha reported only 11.3 B devices (2024). Despite this, Schneier’s concern is still warranted. The core problem identified by Hiller et al. is the systemic insecurity inherent in the modern digital ecosystem. Schneier suggests that IoT devices are often rushed to market with security considerations lacking. Key issues include the absence of industry incentives to prioritize security, insuƯicient regulatory oversight, and a gap in consumer awareness. These factors collectively contribute to an environment where vulnerabilities in everyday devices can be exploited to jeopardize physical safety and national security.

"A rational CEO will choose to save money [on security] or spend it on new features to compete in the market... most of the costs of insecurity will be borne by other parties" (p. 124). Schneier frames this as a "Prisoner’s Dilemma," where companies avoid security costs to maintain competitive pricing, despite the systemic risks. The market favors rapid development and cost savings over robust security (Davy, et al., 2022). Meanwhile, consumers are ill-equipped to demand better protection. Moreso, Hiller et al. explain that the absence of mandatory security standards and oversight exacerbates these issues.

Hiller et al. use real-world incidents and plausible scenarios to illustrate the dangers, including weak default passwords (Naprys, 2025), delayed software updates (Islam, 2023), and omitting encryption for sensitive data (ESG, 2024). Additionally, Schneier portrays his hypothetical “click here to kill everybody” scenario, where a hacked bioprinter created a lethal virus. These examples highlight that IoT insecurity is not just a technical issue, but a societal risk with potentially global consequences.

Alternative Solutions

The alternatives to Hiller et al.’s cybersecurity challenges are as follows. One option is the adoption of voluntary industry standards. These must quickly adapt to technological changes and impose less regulatory burden on manufacturers (Goldstein, 2018). However, Schneier stresses that their eƯectiveness is limited. He illustrates historic examples of manufacturers ignoring security best practices (e.g., Jeep’s delayed patch, D-Link’s deceptive trade practices). Pardis et al. suggests another approach involving increasing consumer awareness (2020). This can empower consumers to make safer choices and raise public pressure on manufacturers (Xiao, 2021). However, the technical complexity of IoT and the information asymmetry thereof makes it diƯicult for consumers to assess device security, warns Schneier. “This asymmetry makes deterrence more diƯicult” (p. 92).

Technical solutions directly address vulnerabilities and can be incrementally adopted by manufacturers. This may involve implementing better encryption and secure coding practices. While these measures are important, Schneier suggests that their adoption is uneven across the industry. Moreso, they cannot resolve the broader systemic issues, he includes. Additionally, Kavinsky explains that the IoT global supply chains and data flows complicate regulation enforcement (2023). Therefore, Schneier suggests mandatory security standards (instead of voluntary) which oƯer a comprehensive, consistent solution where manufacturers are compelled to comply. Nevertheless, regulatory approaches may be slow to adapt to rapid technological change. Moreso, manufacturers may be forced to raise prices for consumers and sacrifice innovation (Emami-Naeini, et al., 2020).

The primary solution advanced by Hiller et al. is an incentive-based tax policy toolkit that includes both tax credits for positive cybersecurity investments and penalties for underinvestment, tailored to entity size and industry. While voluntary standards and consumer awareness campaigns are discussed as alternatives, both the article and Schneier’s work highlight their limitations in the face of complex, evolving threats (Wolf, 2019). Schneier’s advocacy for mandatory standards and product liability complements the article’s call for policy tools that realign private sector incentives with the public good.

Conclusion

The “carrots and sticks” incentive-based framework outlined by Hiller et al. presents a practical and balanced solution to the chronic underinvestment in cybersecurity. By combining tax credits for proactive security measures with penalties for noncompliance, this approach directly addresses the market failures and misaligned incentives that have left many small and medium-sized businesses of whom are vulnerable to attack.

Schneier’s examples of IoT and infrastructure breaches reinforce the urgency of adopting such systemic reforms. While voluntary standards and consumer education remain helpful, both Hiller et al. and Schneier demonstrate these alone are insuƯicient for today’s rapidly evolving cyber risks. Ultimately, the “carrots and sticks” strategy oƯers a promising path to realign incentives, foster accountability, and build a more resilient digital ecosystem.

Bibliography

Davy, T., Dholiwar, V., Carr, M., Maidment, D., Costante, E., & Eaves, S. (2022, 1 1). The IoT Industry Action Plan to Reduce the Cost of Security. Retrieved from psacertified.org: https://www.psacertified.org/app/uploads/2022/08/Confidence_to_Create_Advisor y_Paper_PSA_Certified-1-compressed.pdf

Duarte, F. (2024, 2 19). Number of IoT Devices (2024). Retrieved from explodingtopics.com: https://explodingtopics.com/blog/number-of-iot-devices

Emami-Naeini, P., Dheenadhayalan, J., Agarwal, Y., Cranor, L. F., CMU, & CyLab. (2020). Which Privacy and Security Attributes Most Impact Consumers’ Risk. FTC PrivacyCon CyLab. Pittsburg, PA: Carnegie Mellon University, CyLab.

ESG. (2024). ESG Report Operationalizing Encryption and Key Management. fortanix.com. Retrieved from https://resources.fortanix.com/esg-report-operationalizingencryption-and-key-management

Goldstein, P. (2018, 3 27). Will There Be a Government Standard for IoT Security? Retrieved from fedtechmagazine.com: https://fedtechmagazine.com/article/2018/03/willthere-be-government-standard-iot-security

Hiller, J., Kisska-Schulze, K., & Shackelford, S. (2024). Cybersecurity Carrots and Sticks. American Business Law Journal 61, 5-29.

Islam, M. A. (2023, 5 23). The Risks of Neglecting Software Maintenance and Updates. Retrieved from devs-core.com/: https://devs-core.com/the-risks-of-neglectingsoftware-maintenance-and-updates/

Kavinsky, M. (2023, 11 13). The Regulatory Landscape for IoT: Navigating the Complexities of a Connected World. Retrieved from iotbusinessnews.com: https://iotbusinessnews.com/2023/11/13/84084-the-regulatory-landscape-for-iotnavigating-the-complexities-of-a-connected-world/

Matthews, A. (2017, 1 12). Challenges, solutions and security needs in IoT business plans. Retrieved from electronicspecifier.com: https://www.electronicspecifier.com/products/iot/challenges-solutions-andsecurity-needs-in-iot-business-plans

Naprys, E. (2025, 5 13). 19 billion leaked passwords reveal deepening crisis: lazy, reused, and stolen. Retrieved from cybernews.com: https://cybernews.com/security/password-leak-study-unveils-2025-trends-reusedand-lazy/

Schneier, B. (2018). Click Here to Kill Everybody: Security and Survival in a Hyperconnected World (1st Edition). W. W. Norton & Company. Retrieved from https://www.amazon.com/Click-Here-Kill-Everybody-Hyperconnected/dp/0393608883#detailBullets_feature_div

Sinha, S. (2024, 9 3). State of IoT 2024: Number of connected IoT devices growing 13% to 18.8 billion globally. Retrieved from iot-analytics.com: https://iotanalytics.com/number-connected-iot-devices/

Tjahja, N. (2022, 12 29). Are companies responsible for the security of their digital services and products, and to what extent? Retrieved from diplomacy.edu: https://www.diplomacy.edu/blog/are-companies-responsible-for-the-security-oftheir-digital-services-and-products-and-to-what-extent/

Wolf, C. (2019, 7 1). Book Review: Click Here to Kill Everybody. Retrieved from asisonline.org: https://www.asisonline.org/security-managementmagazine/articles/2019/07/book-review-click-here-to-kill-everybody/

Xiao, Q. (2021). Understanding the asymmetric perceptions of smartphone security from security feature perspective: A comparative study. Telematics and Informatics Volume 58, 101535.

Emerging Technologies Literature Review

James V. Tarlton

5/4/2025

Abstract

This paper presents a comparative analysis of three influential works—Azeem Azhar’s The Exponential Age (2021), Adrian Daub’s What Tech Calls Thinking (2020), and Bernard Henri Lévy’s The Virus in the Age of Madness (2020). The paper interrogate how rapid technological, ideological, and biological change is reshaping society. Additionally, intersections between these works and the philosophies of political scientist Dr. George Friedman are recognized. Azhar explores society’s exponential gap between fast innovation and slow adoption, which parallels Friedmans American institutional and industrial cycles. Daub dissects Silicon Valley’s self-mythologizing and selective amnesia, which parallels Friedman’s observation of how ideology has shaped institutions that prioritize capital over democracy. Lévy critiques the elevation of medical authority and the reduction of liberties during the COVID-19 pandemic, which parallels Friedman’s critique of a disconnected technocracy. Through examination of these intersections and divergent arguments, this study reveals a shared concern about the dangers of unchecked power and the erosion of agency, ethical responsibility, and democratic oversight in times of disruption and crisis.

Introduction

Society has recently entered a period of rapid technological, ideological, and biological change. Innovations are reshaping society at an exponential pace. However, longstanding institutions, legal frameworks, and cultural norms are struggling to keep up, creating what Azeem Azhar terms the “exponential gap.” This widening divide between technological progress and societal adaptation has fueled polarization, inequality, and concentrated power. Meanwhile, the technology industry’s self-mythologizing and selective amnesia serves to obscure historical context, limit critical discourse, and shield companies from accountability, as Adrian Daub argues. Moreso, COVID-19 has exposed vulnerabilities of contemporary society, with BernardHenri Lévy warning against unchecked medical authority, and erosion of democratic debate and civil liberties.

This paper offers a comparative analysis of The Exponential Age by Azeem Azhar (2021), What Tech Calls Thinking by Dr. Adrian Daub (2020), and The Virus in the Age of Madness by Bernard-Henri Lévy (2020), examining how each work interrogates the impact of rapid changes in societal structures, individual agency, and the balance of power. By exploring intersections and divergences in their critiques, this study highlights challenges and ethical dilemmas facing society. Ultimately, these works converge for renewed engagement, ethical vigilance, and collective action to ensure benefits of progress are shared and that democracy and dignity are preserved amidst disruption and crisis. Additional intersections between these works and Geroge Friedman’s socioeconomic philosophy are explored. Friedman’s 80-year institutional and 50-year industrial cycles state that America undergoes political and socioeconomic transformations, respectively (2020).

Analysis and Overview of the Exponential Age

The central themes of The Exponential Age (2021) revolve around the exceptional pace of technological advancement and acute societal challenges thereof. The book introduces the concept of the "exponential gap," (p. 16) which describes rapidly evolving technologies and society's inability to adapt its institutions, laws, and cultural norms. The gap is revealed in political polarization, rising inequality, and unchecked corporate power.

The central themes of The Exponential Age (2021) revolve around the exceptional pace of technological advancement and acute societal challenges thereof. The book introduces the concept of the "exponential gap," (p. 16) which describes rapidly evolving technologies and society's inability to adapt its institutions, laws, and cultural norms. The gap is revealed in political polarization, rising inequality, and unchecked corporate power.

Moreso, Azhar highlights how traditional linear thinking and institutional "path dependence" (p. 110) leave societies ill-equipped for exponential change. He explains that the repercussions of this are that it results in “institutional lag and cultural lag” (p. 87), as seen in the rise of the gig economy, data breaches, and pandemic response.

The Exponential Gap

In Wired (2021), Azhar suggested the gap is created by two forces—"the inherent difficulty of making predictions” and “the inherent slowness of institutional change” (para. 41). Business dynamics have shifted, with big-tech companies leveraging network effects, intangible assets, and platform models to achieve unprecedented scale and dominance. Notably, at the expense of smaller producers and economic dynamism, he adds. Additionally, he argues that these firms exploit global tax loopholes and challenge traditional antitrust frameworks. Thus, affecting labor compensation through shifted tax burdens (Doyle, Carlos, & Serrato, 2024). This, in concert with automation, negatively impacts labor markets (Holzer, 2022). However, Azhar explains that the rise of gig work has brought forth the benefit of increased work flexibility. Though, this type of work is associated with insecurity and inequality; thus, new approaches to labor rights and protections are needed, per NBER (2025).

Wright’s Law vs Moore’s Law

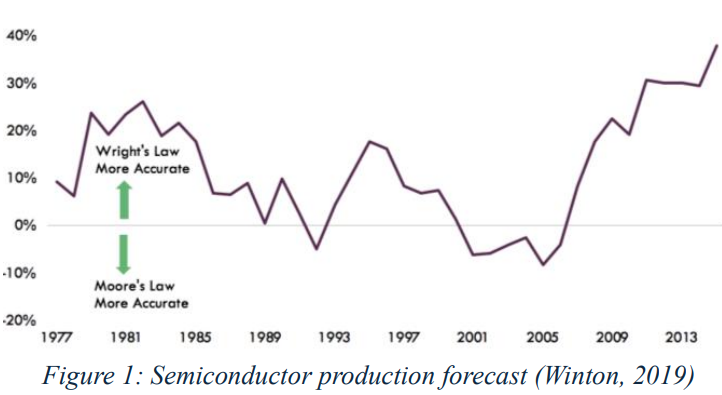

Drivers of Azhar’s exponentiality include global supply chains and freemarket economics. Azhar suggests that the free-market helped drive globalization; and, in turn, globalization helped drive the Exponential Age. He suggests that the Exponential Age can be traced back to the early 1900s with Theodore P. Wright’s analysis of airplane production costs (1936). In fact, experts indicate that Wright’s Law more accurately describes technological evolution when compared to Moore’s Law (McCormick, 2012) (Johnson, 2013) (Winton, 2019) (Figure 1).

The Exponential Gap vs Hype Gap

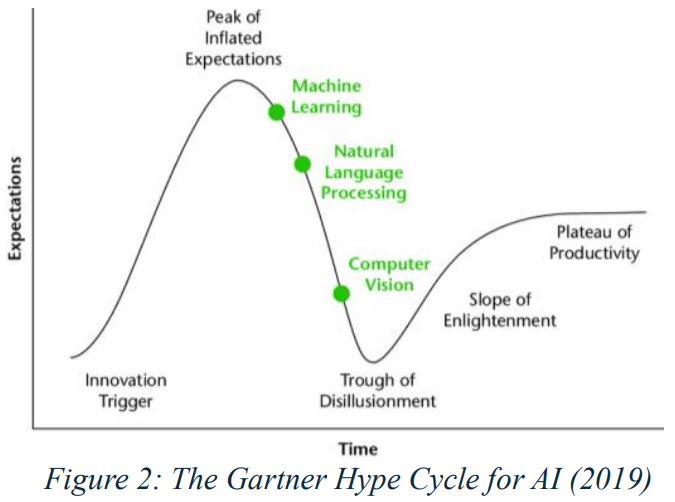

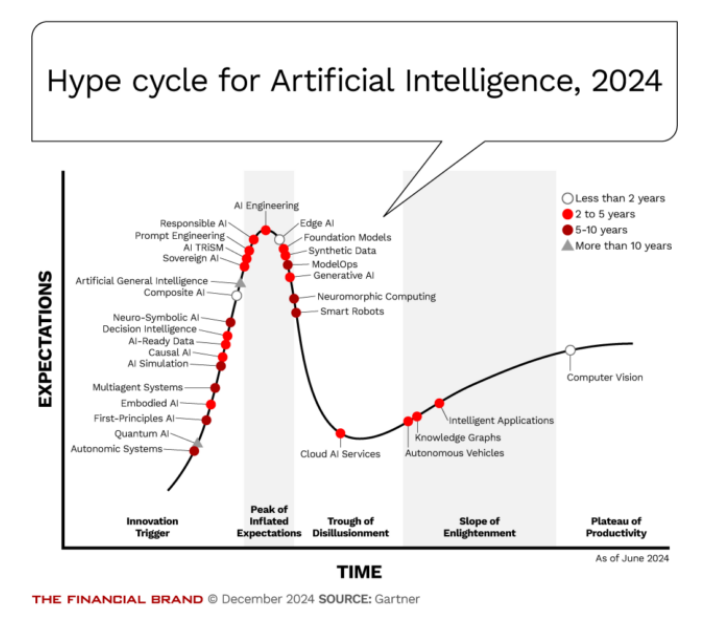

The “Tech Hype Gap” describes when anticipation about a technology precedes its actual usage. Moreso, it highlights the negative social impact of marketing outpacing actual progress (Davis, 2019). This gap is based off the “Gartner Hype Cycle,” which describes the maturity and adoption of technologies over time (Fenn & Linden, 2003). Moreso, Fenn and Raskino explain that overly optimistic expectations can lead to discontent or backlash if a technology does not “live up to the hype” (2008). While the Gartner Hype Cycle originates from overly optimistic marketing claims, particularly for AI (2019) (Figure 2) (Appendix A), the Exponential Gap is caused by technology growth, causing market disruption and societal inequalities. For instance, market disruption is seen through the emergence of online retailers like Amazon displacing brick-and-mortars stores. Moreso, gig work displacing official work exacerbates income inequality (Sankararaman, 2024).

Globalization

The world has entered a third phase of globalization which involves sophisticated, digitized supply chains (Friedman T. , 2005). However, Ahar suggests that, geopolitically, the world is becoming "spiky," with innovation and prosperity concentrated throughout urban centers of wealthy nations. Modern technologies enable local production and fragment global networks into "splinternets" (pp. 206 – 235). In its inception, the Internet was distinctly American but always promised a borderless future. However, cybersecurity, disinformation, and digital warfare have exposed vulnerabilities to government agencies, requiring new norms, cooperation, and resilience in the face of rapidly evolving threats.

The Four Broad Domains

Computing

The computing domain is realizing new GPTs like Artificial Intelligence (AI), Cloud Computing, and Quantum Computing. Therefore, Azhar suggests that new frameworks are needed to ease their transitions. Gartner’s Hype Cycle helps avoid inflated expectations and disillusionment of AI (Coshow, 2024). DevSecOps, an IT project management methodology, avoids vulnerabilities to cybersecurity attacks that organizations might face in the cloud (NIST, 2022). The Quantum Computing Cybersecurity Preparedness Act (2022) ensures resilience of information systems in a post-quantum cryptography Internet (Sanzeri, 2023).

Energy

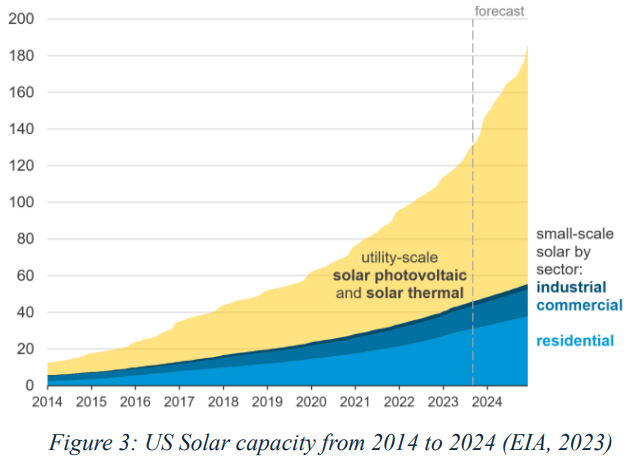

According to a Rockwell Automation survey, energy management is the top sustainability concern for organizations (2025). The energy domain is emerging with new GPTs like next-gen renewables, batteries, and nuclear reactors (Chu & Tarazano, 2025). The solar panel first appeared at Bell Labs in the 1950s, with low efficiency. However, continuous advancements in efficiency and affordability realize a wider adoption (EIA, 2023) (Figure 3). Next generation battery technologies (i.e., sodium-ion, solid-state), offering faster charging and more capacity than their lithium-ion counterparts (DOE, 2025), make electronic vehicles (EVs) safer and more efficient—thus more enticing to consumers (Reuters, 2025). Improvements to nuclear reactor design (Barbarino, 2022) promise advancements in energy production, waste management, and overall societal benefits (WNA, 2021). For instance, experts suggest nuclear power is key to meet the future demands of computational power for AI and data center processing (Calma, 2023) (Browne, 2024).

Biology

DNA synthesis, genomics, and biomanufacturing are novel GPTs in the biology domain highlighting revolutionary evolution in the exponential age. Recent advances in automated DNA synthesis enable the creation of new DNA sequences for various applications. Patents surrounding DNA Synthesis reached approximately 472 thousand filings in 2023. This suggests wide scientific community adoption and use (Wellspring, 2024). Regarding genomics, long-read sequencing techniques (e.g., Oxford Nanopore) offer unprecedented accuracy and accessibility. For instance, the SmidgION brings laboratory-grade sequencing to mobile devices (Wang, et al., 2021). Industry 4.0 and the Industrial Internet of Things (IIoT) are key determinants in the future state of biomanufacturing (Dikicioglu & Borgosz, 2024). Concepts like soft sensors aid in the digitization of bioprocessing (Rathore, Nikita, & Jesubalan, 2022).

Manufacturing

Smart manufacturing, additive manufacturing, and cloud-based supply chains are revolutionizing manufacturing for organizations. Worldwide, companies continuously increase their technology budgets to integrate smart manufacturing equipment into their factories (Rockwell Automation, 2025). Additive manufacturing, or 3D printing, is enabling manufacturers to become more agile by harnessing rapid prototyping of new designs and concepts (Chen & Lin, 2019). Additionally, this approach allows manufacturers to explore new material science breakthroughs with varieties of additive polymers (King, 2022). Regarding cloud-based supply chains, GenAI integrations are the top technology investment for manufacturing companies (Gartner, 2025).

Institutional and Cultural Lag

Azhar defines institutional and cultural lag in terms of the organizational and societal implications they can have such as political division, inequality, and unchecked power. Similarly, the ends of George Friedman’s cycles (i.e., 80-year institutional, 50-year industrial), each predict political and economic disruption, respectively (2020). The late 2020s are unique in that these 80- and 50-year cycles will converge amid the “exponential age.”

Prior to The Great Depression, William Ogburn observed lag associated with the introduction of industrial machinery and automobiles (1922). Rick Maurer points to other examples of institutional and cultural lag within the information technology realm including resistance to change and digital literacy, respectively (2010). In fact, according to a Gartner survey, 80% of all data breaches within organizations are caused by misconfigured systems and 99% of cloud failures are attributed to human error (Panetta, 2019). This suggests a knowledge gap (or lag) in workforces throughout organizations (Chaudhary, 2023).

Implications

Azhar’s “exponential gap” reflects the widening divide Friedman describes in his socioeconomic cycles. Both warn that unchecked, exponential growth risk overconsumption, systemic instability, and further concentration of power. However, he also emphasizes that society can shape these outcomes through deliberate choices, updated policies, and new institutions focused on transparency, digital rights, and building shared digital commons. From an IT perspective, if an organization lags, it risks operational inefficiencies (e.g., outdated software, hindered automation), financial risks (e.g., accounting compliance issues, lost opportunities), and security risks (e.g., malware, data breaches) (Byrd, 2024). Finally, Lauren Arcuri suggests that technological advancements have contributed declining birth rates (2019).

Remedies

Azhar calls for radical thinking and collective action to bridge the exponential gap, harnessing technological change for the common good and ensuring that the benefits of the Exponential Age are widely shared. For example, Florida Governor DeSantis’s Digital Bill of Rights, protects Floridians from the overreach and surveillance of tech giants (FedSoc, 2023). Regarding IT lag, federal agencies housing sensitive data are hesitant to move to the cloud despite their software vendors urging them to do so (Hanna, 2023) (Chao, 2024). To aid in this predicament, the National Institute of Standards and Technologies (NIST) designed the Federal Risk and Authorization Management Program (FedRAMP) framework in alignment with Federal Information Security Modernization Act (FISMA) to ensure US federal agencies can securely use cloud technologies. FedRAMP laid a foundation for companies and other governments to help reduce the risk of data breaches and cyber threats (Blokdyk, 2021). FedRAMP coupled with the DevSecOps IT project management and deployment methodology helps ensure that cloudbased information systems are not prone to vulnerabilities (Arshad, 2023). Regarding declining birth rates, Dr. Karen Guzzo suggests institutionalized pronatalist tactics such as tax benefits or subsidies (2025).

Analysis and Overview of What Tech Calls Thinking

The central themes of Adrian Daub’s What Tech Calls Thinking (2020) revolves around how the technology industry constructs self-referential mythology and worldview by reframing old ideas, selectively forgetting history, and promoting false narratives. Daub argues that these tactics confine critical dialogue and disenfranchise relevant experience. Moreso, he explains that the industry’s embrace of technological determinism serves to justify ethically questionable practices and to minimize accountability.

Mythology and Worldview Construction in Tech

Daub suggests that the technology industry cultivates self-referential mythology by reframing historical ideas as novel where “the myth of precariousness persist[s]” (p. 12). This process involves selectively erasing context to position technological development as an inevitable force rather than a socially contingent process. By obscuring precedents (e.g.,19th century industrialism, 1960s counterculture) technology leaders present governance and labor challenges as unprecedented. They then proceed to stifle meaningful dialogue with critics who draw parallels to past societal shifts, Daub explains. For instance, work by Thiel and Sack at Stanford (1998) explores the groupthink mentality they observed in academia. However, this continues to be observed (Wooldridge, 2023) (Blease, 2023).

Selective Historical Amnesia

Daub suggests that selective amnesia observed within the technology industry enables

companies to dismiss regulatory concerns and ethical critiques. He highlights gig economy

worker rights as clashes between modern tech models and old labor laws, like 20th-century

workplace protection struggles. Moreso, the emergence of online riding sharing platforms has

decreased employment and earnings within the taxi industry, per NBER (2025) and Schneider

(2019) (Figure 4). Additionally, “[c]oding went from being clerical busywork done by women to

a well-paid profession dominated by men” (p. 8). Also, Daub suggests that the historical

precedents for monopolistic practices and privacy encroachments have become minimized.

Technology companies are positioning themselves in uncharted territory; therefore, Daub

suggests the need for new frameworks. Likewise, Kristie Lam of UC San Franciso College

of Law suggests the adoption of antitrust frameworks to ensure data collection practices

no longer violate user privacy, e.g., Klein v. Facebook (2022), (Lam, 2024).

Daub suggests that selective amnesia observed within the technology industry enables

companies to dismiss regulatory concerns and ethical critiques. He highlights gig economy

worker rights as clashes between modern tech models and old labor laws, like 20th-century

workplace protection struggles. Moreso, the emergence of online riding sharing platforms has

decreased employment and earnings within the taxi industry, per NBER (2025) and Schneider

(2019) (Figure 4). Additionally, “[c]oding went from being clerical busywork done by women to

a well-paid profession dominated by men” (p. 8). Also, Daub suggests that the historical

precedents for monopolistic practices and privacy encroachments have become minimized.

Technology companies are positioning themselves in uncharted territory; therefore, Daub

suggests the need for new frameworks. Likewise, Kristie Lam of UC San Franciso College

of Law suggests the adoption of antitrust frameworks to ensure data collection practices

no longer violate user privacy, e.g., Klein v. Facebook (2022), (Lam, 2024).

Technological Determinism as Ideology

Per work by early 20th century sociologist Thorstein Veblen, technological determinism is the belief that technological advancement is inevitable and outside human control. Moreso, it is the belief that tools dictate societal outcomes (McLuhan, 1964). The technology industry’s embrace of technological determinism serves as prophecy and justification. For instance, framing technological advancements (e.g., AI, blockchain) as autonomous forces, technology executives deflect accountability, arguing they merely respond to inevitable progress. This worldview underpins arguments against regulation and ethical oversight, suggests Daub.

However, in a subcommittee hearing regarding the cybersecurity implications of a lacking AI posture within government agencies, the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) notably argued that innovation must not be stifled (2023). Industry experts recommend AI powered risk analysis software to stay secure in cyberspace (IBM) (Cisco). The fact that AI must be fought with AI brings forth a conundrum to governments and organizations (Humble, 2024).

Linguistic Framing and Power Dynamics

Because of its influence on human advancement, innovation is complicated to legislate. Regarding linguistics and dynamics, Daub suggests that “neuro-linguistic programming remains influential today” (p. 144). He states rhetoric behind certain buzzwords (e.g., disruption, scale) launder extractive practices as revolutionary altruism. He explains that these terms create a linguistic ecosystem where criticism becomes semantically impossible to oppose. This is like President Trump’s rhetorical use of “common sense” to establish dichotomy with political opponents (Wodajo, 2025). Whether or not ulterior motives are at play in these accounts, Daub brings forth a relevant conversation. This parallels Friedman’s observation of how neoliberalism has shaped economic and political institutions in ways that prioritize capital over democratic governance (Kottász, 2023).

Repurposing Traditions

Daub suggests that “innovative” technology concepts are recycled versions of older concepts. For instance, he argues that the tech “dropout” myth repackages frontier individualism, masking the role of privilege, e.g., family wealth, elite networks. He explains that these factors enable risk-taking that less privileged students do not have. “It’s worth keeping this sense of dropping out in mind when one considers the mythology of famous tech industry college dropouts” (p. 29), he adds. Gap years (or dropping out altogether) in university enable students to venture into entrepreneurship and explore creativity. Therefore, Michael B. Horn, of the Chistensen Institute, argues that gap years should be made available to all students because of the benefits incurred, i.e., career exploration, personal growth, cultural experiences, reduced burnout (2020).

Commodified Self-Help

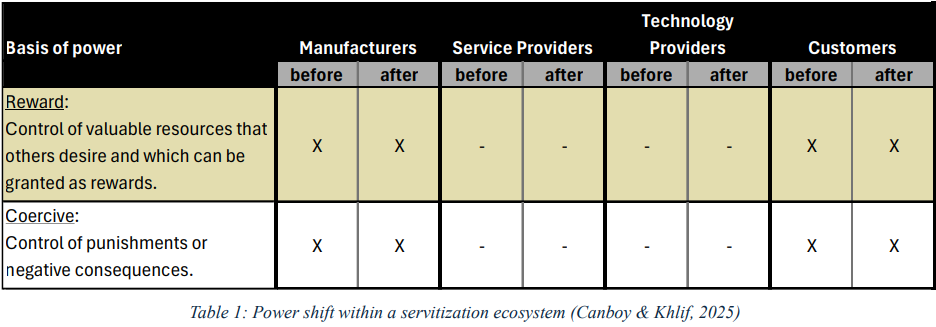

Daub observes that productivity-tracking apps centralize power by being commodified into marketing programs. For instance, a study by Canboy & Khlif (2025) observes the advancing power dynamics across companies that offer productivity-tracking software within servitization ecosystems, e.g., Google, Apple. The authors suggest that servitization can negatively impact customers and manufacturers (Table 1). Servitization is a paradigm shift exposing manufacturers to new revenue streams; however, it can reduce customer ownership and increase customer dependency (Zhang & Banerji, 2017).

Dominance Amongst Platforms

Regarding platform dominance, Daub argues that Silicon Valley has focused on McLuhan-inspired “medium over message” (2001). He explains that this is observed in social media platforms that devalue content. For instance, some experts suggest YouTube’s recommendation algorithm is left-leaning (Ibrahim, et al., 2023) (Dolan, 2023), while others suggest the opposite (Iyer, 2023). By this sentiment, Daub alludes to Marshall McLuhan’s work on cultural transformations and the impact of mass media on societal norms (1964). Other authors’ findings share similar results (Euchner, 2021) (Cole, 2020).

Manipulation of Labor Laws

Daub suggests that social media firms avoid compensating their content creators by categorizing their work as hobbyism. Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act further enables this cost avoidance by absolving platforms of responsibility for hosted content, despite algorithmic amplification of biased or harmful material. Alan Rozenshtein suggests that ambiguities within Section 230 allow platforms to bypass restrictions (2023). Moritz Schramm raises similar concerns about the European Union’s Digital Services Act, arguing that while it aims to set global regulatory standards, it actually grants significant discretion to private entities in its implementation in the pursuit of globalization (2025).

Philosophical Underpinnings and Contradictions

Daub alludes to Ayn Rand’s philosophy of heroic individualism as a staple ideal that permeates technology culture. He suggests that this ideal aestheticizes overworking as passion. Leonard Peikoff shares similar sentiments, suggesting that objectivism frames corporate growth as a moral virtue (1993). Daub explains that this ethos surfaces in founder narratives that celebrate “genius” visionaries while ignoring systemic advantages. For example, the gig economy exemplifies this contradiction, rebranding precarious work as entrepreneurial freedom. Moreso, Daub suggests that Silicon Valley’s celebration of failure, e.g., “fail fast and then iterate” (p. 144), obscures its uneven consequences. For instance, while privileged founders frame setbacks as learning opportunities, marginalized workers face disproportionate fallout from algorithmic layoffs or startup collapses (Faber, Williams, & Skinta, 2024). This selective framing ignores the safety nets (e.g., venture capital, familial wealth, telework capabilities) of privileged workers. For instance, the impact of COVID-19 on labor markets further epitomizes this notion regarding the inequality between white- and blue-collar workers (BLS, 2022).

Open Communication and Its Discontents

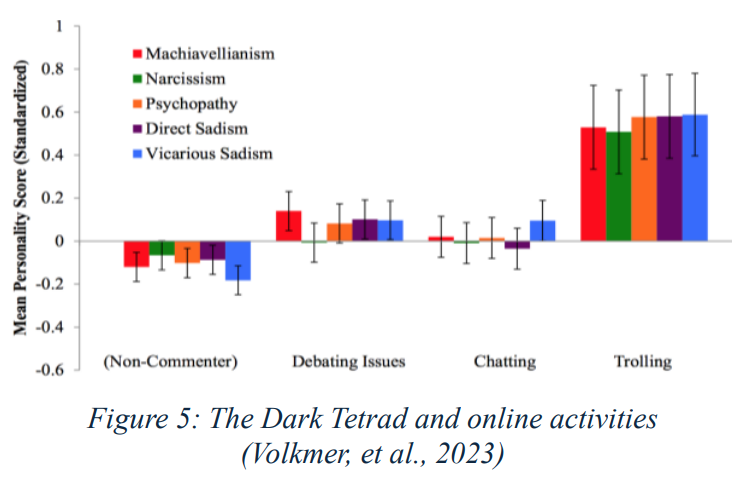

Despite rhetoric about democratizing discourse, engagement-driven platforms often incentivize polarization, explains Daub. He states that tools designed for “connection” frequently amplify abuse and misinformation. For instance, clinical experts suggest that social media causes depression amongst children (Lin, et al., 2016 ) (Miller, 2025). Additionally, Internet trolling emerges as both a byproduct and instrument of this system, describes Volkmer, et al. (2023). They explain that malicious users weaponize free speech to harass others. Furthermore, they suggest a strong correlation (Figure 5) between trolling and the “Dark Terad” of personality (i.e., Machiavellianism, narcissism, psychopathy, sadism) by Buckles, et al. (2013).

Mimetic Desire and Manufactured Conflict

Daub recalls Peter Thiel’s adoption of René Girard’s mimetic theory which frames human desire as imitative. Douglas Green explains how Girad's mimetic theory, when applied to business applications, can forecast consumer behavior and market trends (2025). However, Daub reveals how tech giants manipulate narratives for competitive gain. For instance, by portraying markets as arenas of existential rivalry, technology executives attempt to justify monopolistic practices while minimizing criticisms. This victimhood narrative reinforces Silicon Valley’s self- image as a persecuted visionary class. In fact, Deborah Perry Piscione relates this “ingenuity” to political dysfunction (2013).

Analysis and Overview of Virus in the Age of Madness

Bernard-Henri Lévy’s Virus in the Age of Madness (2020) offers a critique of the societal and governmental responses to the COVID-19 pandemic worldwide. Lévy argues that anxiety and authoritarianism threaten to corrode democratic values, ethical responsibility, and human connection. He also offers insight into the geopolitical dynamics surrounding the pandemic response. Additionally, he calls for a revival of civic discourse and a rejection of reductive views of human life by dissecting the intersection of medical authority, philosophy, and politics.

The Rise of Medical Authority and Democratic Erosion

Medical Gaze and Modern Implications

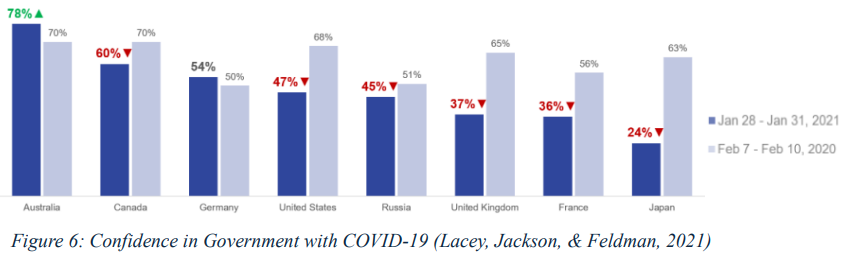

Lévy draws on Michel Foucault’s concept of the “medical gaze” to analyze how the pandemic amplified the influence of doctors and health experts. Foucault discovered perceived connections between knowledge and power within medical industry, arguing that “those in power set the agenda” (1994). Lévy observed this during COVID-19, which led to marginalizing political judgment and democratic oversight. He warns that unchecked authority risks repeating historical abuses (e.g., eugenics) by prioritizing biological survival over civil liberties. Similarly, George Friedman critiques technocrats, disconnected from practical realities, leading to institutional failures in balancing health measures with underlying economic and social costs (2021). In a study analyzing governmental response to COVID, Lacey, Jackson, & Feldman observed a degradation in citizens’ confidence (2021) (Figure 6), implying dissatisfaction.

The Fragility of Scientific Consensus

Contrary to portrayals of science as monolithic, alluded in Griffin Trotter’s journal article about COVID-19 and the “Authority of Science” (2023), Lévy emphasizes its inherent uncertainty and internal conflicts. He argues that treating science as an infallible authority stifles debate, allowing a technocracy to impose policies without transparency or accountability. Friedman suggests that technocrats “live their lives abstractly” and “all [their] problems are intellectual” (2020) (p. 156), which underscores Lévy’s concern about unchecked authority.

Rejecting Romanticization of the Pandemic

Moral and Redemptive Narratives

Lévy criticizes narratives that attribute moral lessons or divine purpose to the virus, calling them intellectually misguided and insensitive to human suffering. He asserts that viruses lack intentionality, and pandemics do not inherently convey virtue or cosmic messages. Likewise, Trotter argues that moral and political stances cannot be derived solely from objective facts (2023). Consequently, this limitation has motivated scientists and policymakers to engage in actions and make statements that undermine the credibility of science, he concludes.

Pragmatism Over Utopianism

Lévy’s philosophy rejects extensive social blueprints and future-oriented idealism in favor of pragmatic, ethical responses to injustice and a defense of liberty (Gardels, 2021). Throughout the book, Lévy advocates for rational, pragmatic debates about pandemic responses, urging societies to weigh concrete costs against the benefits of restrictive measures. These costs may include economic collapse or mental health crises. Lévy rejects utopian visions of societal rebirth, e.g., Fernando, et al. (2022), Yoshihisa & Fernando (2020). On the contrary, Lévy insists that solutions must address immediate human needs rather than broad, abstract ideals.

Critique of Lockdown as Spiritual Retreat

Privilege and Disconnection

Lévy exposes the romanticization of lockdowns as opportunities for self-improvement or spiritual growth, arguing that this view reflects privilege and ignores the struggles of those in poverty, abusive households, or solitary confinement. For marginalized groups, including people with disabilities, isolation exacerbates existing vulnerabilities (Hwang, Rabheru, Peisah, Reichman, & Ikeda, 2020). Critics of Lévy’s work argue that “[i]t can be, at times, difficult to read” (Huminski, 2020) (para. 16) and that he claims the “responses to the coronavirus have been a matter of political psychosis” (McLemee, 2020) (para. 7).

Philosophical Foundations of Engagement

Drawing on existentialist and humanist traditions, Lévy contends that fulfillment arises from engagement with others, not withdrawal. While it may be medically necessary, social distancing risks normalizing alienation and weakening the ethical bonds that sustain communities (Zhu, Zhang, Zhou, Li, & Yang, 2021). Moreso, Lévy depicts a shift from a social contract to a “life contract” that trades liberties for security. This shift is further described as being grounded in mutual rights and responsibilities. He also questions whether this transition is temporary or a precursor to a surveillance-driven future where bodily safety eclipses intellectual, cultural, and spiritual pursuits. Finally, Lévy concludes with a plea to prioritize humanistic values (i.e., compassion, solidarity, intellectual curiosity) over fear-driven conformity. He envisions a future where societies embrace virtues (i.e., risk, complexity, global responsibility) and reject “madness” of authoritarianism.

Global Isolationism and Abandoned Solidarity

Retreat from Global Engagement

Lévy laments how Western societies turned inward

during the pandemic, neglecting ever-present global crises

such as poverty. He argues that this isolationism contradicts

the interconnected reality of modern life and undermines

moral obligations to vulnerable populations. Moreso, AMA

Journal of Ethics researchers suggest that people with disabled

embodiment were particularly isolated from pandemic-induced confinement (Atkins & Das,

2022). Additionally, he suggests that the pandemic accelerated the adoption of digital

surveillance tools. Alongside this observation, a Deloitte survey found organizations’ technology

budgets increase amid the pandemic (2021) (Figure 7). By governments normalizing intrusions

into private life under the guise of public health, Lévy warns that such measures could outlast the

crisis, enabling perpetual authoritarianism under the banner of safety. This parallels prior

concerns about the USA Patriot Act’s impact on privacy, e.g., Pattat (2023), Li (2021).

Lévy laments how Western societies turned inward

during the pandemic, neglecting ever-present global crises

such as poverty. He argues that this isolationism contradicts

the interconnected reality of modern life and undermines

moral obligations to vulnerable populations. Moreso, AMA

Journal of Ethics researchers suggest that people with disabled

embodiment were particularly isolated from pandemic-induced confinement (Atkins & Das,

2022). Additionally, he suggests that the pandemic accelerated the adoption of digital

surveillance tools. Alongside this observation, a Deloitte survey found organizations’ technology

budgets increase amid the pandemic (2021) (Figure 7). By governments normalizing intrusions

into private life under the guise of public health, Lévy warns that such measures could outlast the

crisis, enabling perpetual authoritarianism under the banner of safety. This parallels prior

concerns about the USA Patriot Act’s impact on privacy, e.g., Pattat (2023), Li (2021).

Sanitized Society vs. Human Condition

The book contrasts risk-averse doctrine with the human condition, which thrives on connection and courage. Lévy warns that excessive focus on physical safety jeopardizes creating a sterile, dehumanized world. Lévy urges society to resist reducing life to mere survival, advocating instead for democratic renewal rooted in ethical vigilance. This requires challenging medical and technological overreach while preserving spaces for dissent and debate. Also noteworthy, in a society with an already decreasing birth-rate, COVID-19 further exacerbated the decline (Kearney & Levine, 2023).

Point-Counterpoint

The three books—The Exponential Age (2021) by Azeem Azhar, What Tech Calls Thinking (2020) by Adrian Daub, and The Virus in the Age of Madness (2020) by Bernard-Henri Lévy—each explore how rapid technological, ideological, and biological forces disrupt societal structures. However, their critiques and solutions diverge in scope and focus. Each grapples with the tension between progress and human agency, but through distinct lenses. Azhar emphasizes institutional lag in the face of exponential technology, Daub deconstructs Silicon Valley’s self- mythologizing, and Lévy warns against medical authoritarianism and societal division during crises. Each work intersects with Friedman’s socioeconomic and geopolitical philosophies surrounding technocratic oversight.

Power Dynamics and Institutional Failure

Azhar and Lévy highlight how concentrated power, whether in tech giants or medical authorities, manipulate systemic gaps. Azhar’s exponential gap theory argues that institutions fail to regulate tech-driven economic shifts. Which enables monopolies, erosion of labor rights, and hinders democratic oversight. Similarly, Lévy critiques the medical gaze surrounding COVID19. This involves unchallenged public health mandates and authoritarian overreach. Daub complements this by exposing how the technology industry’s narrative of inevitability masks corporate regulatory evasion as revolutionary progress. All three authors concur that unchecked power flourishes when society lacks frameworks to balance rapid change with ethical liability.

Mythmaking vs. Reality

Daub and Azhar explore narratives used to justify disruption. Daub traces technology’s reliance on recycled philosophies (i.e., Ayn Rand’s individualism, Marshall McLuhan’s medium- centralism) to describe exploitation, such as gig work framed as self-expression. Meanwhile, Azhar shows how technology firms promote marketing hype based on exaggerations, e.g., Gartner’s AI Hype Cycle. Each author reveals disconnects between technology’s perception and its impacts on society. Lévy extends this critique with examples about the COVID-19 pandemic. He rejects romanticization of government-mandated lockdowns. He also condemns the divide between privileged decision makers and those suffering economic or isolationist harm.

Human Agency in Crisis

While Azhar and Lévy advocate proactive solutions to systemic risks, their approaches differ. Azhar calls for collective action to bridge the exponential gap through a digital bill of rights, reformation of antitrust, and green-cautious technology investments. However, Lévy prioritizes philosophical resistance. This entails a revival of democratic engagement, rejection of survivalist paranoia, and reassertion of ethical obligations. Daub is skeptical of technology’s capacity for self-correction. Thus, he urges society to contend with industry’s selective amnesia. But, instead, to learn from mistakes of the past. All three books underscore the need to replace passive acceptance of disruption with deliberate oversight.

Divergent Scopes of Critique

Azhar’s work is macroeconomic and geopolitical, analyzing how computing, energy, biology, and manufacturing are reshaping society. Daub’s focus is cultural, dissecting technology’s intellectual pretensions and their social costs. Lévy’s critique is existential, associating pandemic responses to a broader erosion of humanistic values. Yet he overlaps Daub’s analysis of technology’s mimetic desire and mirrors Azhar’s warnings about splinternet fragmentation. While Lévy’s warnings about isolationism resonate with Azhar’s observations on declining global cooperation. Together, they describe the world’s struggles in reconciling progress. Each author agrees that solutions require ingenuity and a reaffirmation of humanity.

Public Reception of Works

The Exponential Age

When released, Azeem Azhar’s The Exponential Age was met with commendation for its well-reasoned analysis, relevance, and constructive outlook (Smith P. , 2021). Azhar’s book is considered a significant contribution to the public discourse on technology’s role in shaping the future. It offers a roadmap to navigate exponential change. His work is accessible and relevant to a broad audience (Turck, 2022). Reviewers highlight his ability to synthesize multiple disciplines (e.g., physics, economics, political science) (Rotman, 2021).

What Tech Calls Thinking

Adrian Daub’s What Tech Calls Thinking was well-received as a rigorous critique of Silicon Valley’s ideological base. Critics value the book for its historical and philosophical insights. Daub recommends the book to readers seeking to understand the myths and ideas shaping culture and technology (Adams, 2020). Though, it received criticism for its academic perspective (Seidl, 2020), and being too broad with fundamental concepts (Lundblad, 2021).

The Virus in the Age of Madness

While Bernard-Henri Lévy’s earlier works were often criticized for factual inaccuracies, misuse of sources, and grammatical mistakes, Virus in the Age of Madness has received approval from critics and appeal from readers (Smith B. , 2021). Some reviewers focus on the book’s argumentative style, rhetoric, contradictions, and philosophical questions (Kirkus Reviews, 2020). In retrospect, Lévy’s criticisms are exacerbated with the Trump White House’s recent claims the virus’s origins (WhiteHouse.gov, 2025). Moreso, with recent claims about the Biden administration’s efforts to suppress evidence about the pandemic’s origins and engage in a campaign of “delay, confusion, and non-responsiveness” (Rubin, 2025) (para. 5).

Friedman Intersections

Azhar

Azhar’s work on the exponential pace of technological change and the institutional lag thereof relates to Friedman’s insights on socioeconomics and the challenges that emerged in the US post WWII with a technocratic governance absorbed with theory instead of pragmatism. Both highlight the need for adaptive, accountable institutions capable of managing rapid change to prevent social and political crises. Moreso, Azhar’s exponential gap reflects the widening divide Friedman describes in his institutional and industrial cycles.

Daub

Daub’s work relates to Friedman’s by critically examining the ideological and institutional forces that shape contemporary technological and political power. Both highlight the risks posed by technocratic and neoliberal elites who promote narratives of inevitability that obscure democratic deficits. Moreso, by promoting individualism that masks social inequalities. Their combined insights deepen understanding of how cultural mythology and institutional dynamics interact to influence governance and societal outcomes in the age of rapid technological change.

Lévy

Lévy’s work relates to Friedman’s by providing a philosophical and political critique of institutional overreach and the resulting democratic crises during the pandemic. Both call for renewed representative oversight and ethical vigilance to counterbalance the dominance of shortsighted expert authority in times of societal upheaval. Lévy emphasizes the danger of infallible scientific consensus, which stifles debate and accountability. Friedman similarly notes that reliance on expert authority without checks and balances generates political divide.

Key Takeaways

The Exponential Age by Azeem Azhar, What Tech Calls Thinking by Adrian Daub, and The Virus in the Age of Madness by Bernard-Henri Lévy each examine the impact of rapid change on society—whether technological, ideological, or biological. Despite their differing subjects, all three books converge to circumvent disruptive forces at play against society through ethical vigilance and collective action.

Rapid Change Outpaces Institutions

Azhar’s The Exponential Age highlights the widening divide between technological innovation and society’s ability to adapt its laws, institutions, and cultural norms. However, there is a lag in this adaptation (i.e., the exponential gap) which results in rising inequality, unchecked corporate power, and systemic vulnerabilities. The gap can be seen in the gig economy, data privacy, and pandemic responses. Azhar calls for collective action and new frameworks to ensure that the benefits of exponential technologies are broadly shared. Moreso, to ensure that these technologies do not entrench the power of large technology corporations.

Tech Mythology and Accountability

Daub’s What Tech Calls Thinking dissects how the technology industry constructs selfserving myths. In other words, repacking old ideas as revolutionary, promoting narratives of inevitable progress, and glorifying individualism. This mythology obscures historical context, limits accountability, and perpetuates privilege (or lack thereof). This is articulated in the gig economy and college dropout examples. Finally, Daub warns that technology’s selective amnesia and platform primacy enable exploitation, devalue labor, and allow companies to evade responsibility for societal harms.

Authority, Freedom, and Human Values in Crisis

Lévy’s The Virus in the Age of Madness critiques the elevation of medical authority and the reduction of life to biological survival during the COVID-19 pandemic. He warns that unchecked medical and technological power can erode democratic debate, civil liberties, and ethical engagement. Lévy rejects the romanticization of lockdowns, instead calling for pragmatic, humane reactions. He calls for responses that prioritize social bonds, intellectual life, and global responsibility to the vulnerable.

Shared Themes and Contrasts

All three books caution against the dangers of unchecked power within technology corporations, medical authorities, or platform owners. They also express warning against the erosion of democratic oversight and ethical responsibility. Each author emphasizes the importance of historical awareness and critical thinking. Moreso, they highlight the need to resist narratives that frame disruption as inevitable or virtuous.

While Azhar is optimistic about the potential for society to shape technological outcomes through policy and collective action, Daub is more skeptical of the technology industry’s willingness to correct itself. Lévy is concerned about the loss of humanistic values in the face of crisis. However, the books collectively argue for the reclamation of agency to ensure that progress serves the betterment of society. The authors call upon individuals, communities, and institutions to impose moral foundations. Rather than reinforcing privilege, isolation, or authoritarian control.

Concluding Thoughts

In summary, the analysis and contrast between The Exponential Age, What Tech Calls Thinking, and The Virus in the Age of Madness reveal three distinct but connected critiques of how modern society responds to rapid change. All three books criticize the consequences of rapid technological, ideological, and biological change. Moreso, each book intersects philosophies of Dr. Geroge Friedman. Azhar analyzes institutional lag and economic disruption—paralleling Friedman’s American institutional and industrial cycles. Daub dissects the cultural narratives and myths of the technology industry—paralleling Friedman’s geopolitical and institutional analysis of technocracy and neoliberalism. Lévy warns of the philosophical and ethical dangers of crisis-driven authority—paralleling Friedman’s political critique of technocratic overreach. While each book differs in scope, they emphasize the need for criticism, vigilance, and unity. And together, they seek to ensure progress serves humanity rather than entrenching power and inequality.

Appendices

Appendix A

Bibliography

Abraham, K. G., Haltiwanger, J., Hou, C., Sandusky, L. K., & Spletzer, J. (2025). Driving the Gig Economy. NBER Working Paper No. w32766, 1-48. Retrieved from https://ssrn.com/abstract=4915953

Adams, J. (2020). What Tech Calls Thinking: Book Review. Retrieved from medium.com: https://journojoshua.medium.com/what-tech-calls-thinking-book-review-91ca4fb248e8

Arcuri, L. (2019). 4 Contributing Factors to Declining Fertility Rates: A Global Overview. Retrieved from GE HealthCare

Voluson Club: https://www.volusonclub.net/empowered-womens-health/4-contributing-factors-to-declining-fertilityrates-a-global-overview/

Arshad, R. (2023). Improving Cloud Security with DevSecOps: Best Practices for Azure. Retrieved from medium.com: https://medium.com/@arshriz/best-practices-for-implementing-cloud-native-devsecops-in-azure-13a9062cee92

Atkins, C. G., & Das, S. (2022). What Should Clinicians and Patients Know About the Clinical Gaze, Disability, and Iatrogenic Harm When Making Decisions? AMA Journal of Ethics.

Azhar, A. (2021). The Exponential Age. Diversion Books.

Azhar, A. (2021). The Exponential Age Will Transform Economics Forever. Retrieved from wired.com: https://www.wired.com/story/exponential-age-azeem-azhar/

Barbarino, M. (2022). What is Nuclear Fusion. Retrieved from iaea.org: https://www.iaea.org/newscenter/news/what-is-nuclearfusion

Blease, C. (2023). Groupthink is stifling the university. Retrieved from spiked-online.com: https://www.spikedonline.com/2023/04/26/groupthink-is-stifling-the-university/

Blokdyk, G. (2021). FedRAMP: A Complete Guide. 5STARCooks.

BLS. (2022). The Impact of COVID-19 on Labor Markets and Inequality. Bureau of Labor Statistics Working Paper 551, 1-37. Retrieved from https://www.bls.gov/osmr/research-papers/2022/pdf/ec220060.pdf

Browne, R. (2024). Why Big Tech is turning to nuclear to power its energy-intensive AI ambitions. Retrieved from cnbc.com: https://www.cnbc.com/2024/10/15/big-tech-turns-to-nuclear-energy-to-fuel-power-intensive-ai-ambitions.html

Buckles, E., Jones, D., Paulhus, D. L., a, b, c, . . . e. (2013). Behavioral Confirmation of Everyday. APS 24-11, 2201–2209.

Byrd, J. (2024). 9 Signs It’s Time to Upgrade Your ERP. Retrieved from mdm.com: https://www.mdm.com/article/featured/featured-main/9-signs-its-time-to-upgrade-your-erp/

Calma, J. (2023). Microsoft is going nuclear to power its AI ambitions. Retrieved from theverge.com: https://www.theverge.com/2023/9/26/23889956/microsoft-next-generation-nuclear-energy-smr-job-hiring

Canboy, B., & Khlif, W. (2025). Beyond efficiency: Revisiting AI platforms, servitization and power relations from a critical perspective. International Journal of Production Economics, 109550.

Chao, B. (2024). SAP Introduces Financial Incentives to Encourage Hong Kong Companies to Move to the Cloud. Retrieved from news.sap.com/: https://news.sap.com/hk/2024/02/sap-introduces-financial-incentives-to-encourage-hong-kongcompanies-to-move-to-the-cloud

Chaudhary, A. (2023). Managing Cloud Misconfigurations Risks. Retrieved from cloudsecurityalliance.org: https://cloudsecurityalliance.org/blog/2023/08/14/managing-cloud-misconfigurations-risks

Chen, T.-C. T., & Lin, Y.-C. (2019). A three-dimensional-printing-based agile and ubiquitous additive manufacturing system. Robotics and Computer-Integrated Manufacturing, 88-95. Retrieved from https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0736584517302594

Chu, E., & Tarazano, D. L. (2025). A Brief History of Solar Panels. Retrieved from Smithsonian Magazine: https://www.smithsonianmag.com/sponsored/brief-history-solar-panels-180972006/

Cisco. (2025). 2025 Annual Report. Retrieved from cisco.com: https://www.cisco.com/c/en/us/products/security/state-of-aisecurity.html

Cole, J. (2020). Marshall McLuhan and Cultural Studies. Retrieved from winnsox.com: https://winnsox.com/journal/article/marshall-mcluhan-and-cultural-studies

Congress, 1. (2022). H.R.7535 - Quantum Computing Cybersecurity Preparedness Act. Washington DC: 117th Congress.

Coshow, T. (2024). Build AI Agent Services to Revolutionize Client Operations. Gartner. Retrieved from https://www.nice.com/lps/rpcs-gartner-ai-agents?utm_campaign=NL_Q125_EN_PLT_GLOB_243695_CLP_RPCSGartner-Build-AI-Agent&utm_source=google&utm_medium=cpc&utm_content=0295424&utm_detail=dentsu-allus_ca-gartner&gad_source=1&gbraid=0AAAAACq5q8EEDdxtZgrEnq-kC

Daub, A. (2020). What Tech Calls Thinking: An Inquiry into the Intellectual Bedrock. FSG Originals.

Davis, D. (2019). Why We Must Reckon With The Tech Hype Gap. Retrieved from Forbes Communications Council: https://www.forbes.com/councils/forbescommunicationscouncil/2019/07/05/why-we-must-reckon-with-the-tech-hypegap/

Deloitte. (2021). Maximizing the impact of technology investments in the new normal. Retrieved from CIO Insider: https://www2.deloitte.com/us/en/insights/focus/cio-insider-business-insights/impact-covid-19-technology-investmentsbudgets-spending.html

Dikicioglu, D., & Borgosz, L. (2024). Internet of Things: A New Era for Biomanufacturing. Retrieved from thechemicalengineer.com: https://www.thechemicalengineer.com/features/internet-of-things-a-new-era-forbiomanufacturing/

DOE. (2025). Breaking It Down: Next-Generation Batteries. Retrieved from Energy.gov: https://www.energy.gov/eere/ammto/breaking-it-down-next-generation-batteries

Dolan, E. W. (2023). YouTube’s recommendation system exhibits left-leaning bias, new study suggests. Retrieved from psypost.org: https://www.psypost.org/youtubes-recommendation-system-exhibits-left-leaning-bias-new-study-suggests

Doyle, C., Carlos, J., & Serrato, S. (2024). Best-laid plans: How multinationals minimize taxes. Retrieved from stanford.edu/publications: https://siepr.stanford.edu/publications/policy-brief/best-laid-plans-how-multinationalsminimize-taxes

EIA. (2023). STEO Between the Lines: Small-scale solar accounts for about one-third of U.S. solar power capacity. Retrieved from eia.gov: https://www.eia.gov/outlooks/steo/report/BTL/2023/09-smallscalesolar/article.php

Euchner, J. (2021). Marshall McLuhan and the Next Normal. Research-Technology Management , 9-10.

Faber, S., Williams, M. T., & Skinta, M. (2024). Power, discrimination, and privilege in individuals and institutions. Frontiers in Sociology.

FedSoc. (2023). Are Digital Bills of Rights A Sound Solution to Conflict Among Tech Companies, Consumers, and Government? Retrieved from fedsoc.org/commentary: https://fedsoc.org/commentary/fedsoc-blog/are-digital-bills-of-rights-a-soundsolution-to-conflict-among-tech-companies-consumers-and-government

Fenn, J., & Linden, A. (2003). Understanding Gartner's Hype Cycles. Gartner Reserach.

Fenn, J., & Raskino, M. (2008). Mastering the Hype Cycle: How to Choose the Right Innovation at the Right Time. Harvard Business Review Press.

Fernando, J. W., Burden, N., Judge, M., O’Brien, L. V., Ashman, H., Paladino, A., & Kashima, Y. (2022). Profiles of an Ideal

Society: The Utopian Visions of Ordinary People. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology Volume 54, Issue 1, 43-60.

Foucault, M. (1994). The Birth of the Clinic: An Archaeology of Medical Perception. Vintage.

Friedman, G. (2020). The Storm Before the Calm. Doubleday.

Friedman, G. (2021). The 2020s and the Rebuilding of America. (C. C. podcast, Interviewer)

Friedman, T. (2005). The World is Flat. Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Gardels, N. (2021). The Last Humanist. Retrieved from Noema Magazine: https://bernard-henri-levy.com/en/the-last-humanist/

Gartner. (2019). Gartner Hype Cycle for Artificial Intelligence. Retrieved from gartner.com: gartner.com/smarterwithgartner